This is a page for essays (not academic papers) and commentary upon the state of teaching medical English, particularly within Asia. If readers wish to post an item, please send it through the contact us page and, after checking and possible editing, it will be posted.

Essay 3: The ‘Medical Humanities’ — Should healthcare English teachers adopt this ‘holistic’ approach?

The notion of English teachers as being primary agents in the practice of teaching the ‘Medical Humanities’ (MH) has been gaining traction worldwide in recent years. If I could sum up what is meant by the term, it would look something like this: The medical humanities refers to the confluence of social, interpersonal, cultural communication skills and a holistic understanding of the patient-healthcare worker relationship in a manner that goes beyond the strata of purely clinical communication.it attempts to join the produce of the Humanities (Art, Languages, Sociology etc.) with the scientific/clinical perspective of healthcare workers. A number of assumptions and ideas have been included under the umbrella of the term the ‘medical humanities’ and, here, I’d like to list some of the positive, as well as problematic, notions I can see within the domain.

The valuable:

1. At the recently concluded EALTHY Conference in Spain, Dr. Jim Parle of Birmingham University (U.K.) claimed that clinicians should recognize that patients are not ‘objects’ or ‘cases’ but are actually experts in the field of themselves!

2. Above and beyond the traditional focus upon generating a diagnosis, clinicians should be aware that the greatest concern for patients is not just knowing what the diagnosis is but what this means for their lives, including management and follow-up — how will it affect them fully as a person? How will it impact their daily lives? How can it be managed and at what personal cost?

3. ‘Taking’ a history should be seen more as a collaborative process between patient and clinician and not merely as a series of Q-A as if it were an interview. History taking should be a matter of eliciting the patient’s story, allowing the patient to generate a narrative, rather than being a doctor-centered line of inquisition.

4.Gaining the patient’s trust to elicit personal/private/sensitive information, through implicit or direct request for consent, is a skill that doctors should learn to master. Using open-ended interpersonal skills, as opposed to closed question formats, should be encouraged. ‘Tell me more about that’ becomes (perhaps) the most common and helpful healthcare worker utterance.

5. The ICE formula (eliciting the patient’s Ideas, Concerns, and Expectations) should serve as the fundamental ‘template’ for history taking. More of the doctor’s time is spent listening rather than asking questions in such a scenario.

6. False empathy, such as the popular ‘I have a slight fever’ ‘Oh! I’m so sorry to hear that’ type of exchanges should be discouraged.

The questionable:

1. Often, the implicit assumption made by proponents of MH is that those of us with background in the humanities are more sensitive, aware, moral, and humane than those who come from STEM backgrounds. STEM people, the subtext seems to say, need our input to understand people’s feelings and to create more interpersonally effective communication and holistic care. As if STEM people are either insensitive or oblivious to these factors and thus require ‘our’ help. I, for one, do not buy this at all and I think it panders to outdated and negative stereotypes while allowing those of us from the humanities to pump our own chests.

2. While English teachers should be expected to understand how effective communication is constructed (especially in a foreign language), very few of us have the counselling or psychological backgrounds needed in order to feel comfortable about including such content in our teaching arsenal. We are not experts in sociology, philosophy, anthropology etc. and we should not assume to enter that territory with any authority. Let’s not overstep our bounds under the assumed banner of our ‘greater humanity’.

3. Concerns about the nomenclature (e.g. that ‘history taking’ is a presumptuous term and that ‘eliciting the patient’s story’ is preferable) seems to me to be window dressing of the virtue-signalling variety. The reality of the speech event or interaction is the same thing regardless as to how we label it.

4. Given the time limits and stressful workload that most doctors face, is it reasonable to believe that they should be behaving like counselors, spending a lot of time trying to suss out each patient’s ‘story’. Is it realistic? Doctors are not social workers.

5. In some respects, I don’t think MH crosses cultures particularly well. Even indirect attempts at prying into the ‘deeper’ personal aspects of a patient’s life will surely be viewed as intrusive and inappropriate by many Japanese (and other Asian) patients. Many, if not most, might want, prefer, and expect the standard Q&A routine. The doctor should stay in his/her territory and not assume other ‘roles’. This is extremely important within East Asian milieus.

6. I’ve asked several clinicians and medical students how they rank the following qualities among doctors: a) Communication skills b) Clinical knowledge c) Hands-on skills d) Humanitarian principles. ‘D’ almost always comes in last. If you’re not convinced, imagine that you are a patient facing a life-threatening operation. Which 2 are your priorities? Of course ‘D’ might be more of a concern if and when choosing a GP for long-term purposes but, again, this does not suit most Asian clinical milieus.

Essay 2: Are EMP Teachers Ignoring the Horizontal Axis of Medical Discourse?Michael Guest, University of Miyazaki (Japan)

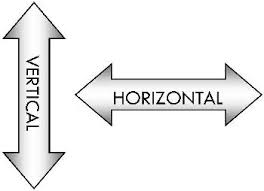

Have medical English teachers largely neglected horizontal communication in favour of the vertical? What I am referring to here is doctor-to-doctor (or health professional-health professional) discourse (representing the horizontal axis), as opposed to doctor/health professional – to – patient discourse (representing the vertical axis). From what I have seen in textbooks and heard in presentations, observations, and discussions with medical English teachers, particularly in Asia, it seems that the great weight of teaching has fallen upon the vertical.

Perhaps this is because many medical English teachers (whether local or so-called ‘native English’ speakers) come from backgrounds outside of healthcare fields and, as such, their view of medical discourse is often coloured by the patient’s perspective – having only been patients themselves.

As a result, our teaching may tend to emphasize doctor-patient discourse, generally focusing upon history taking, a staple of most medical English curricula. History taking is, of course, an essential clinical skill, one that has washback value extending into the learner’s first language and culture. It should be a part of any EMP curricula. However, we might want to consider the likelihood of treating patients who don’t speak the lingua franca of the hospital/country. Unless one works in an accredited international hospital or an area noted for medical tourism the chances of such doctor-patient encounters will likely be low.

Medical discourse has both vertical and horizontal dimensions

For example, in my own institution (in Japan) most requests for upgrading in English skills from clinicians arises from their wishes or concerns about applying these skills on the horizontal axis of discourse. As very few medical tourists or non-Japanese speaking patients visit our hospital, the greater instrumental value for our clinicians lies on the peer-to-peer horizontal axis – the need for professional development or to become active participants in the medical discourse community. This is also true when training health professionals before going abroad for research or practice.

The most obvious of these horizontal discourses are specialized peer-peer functions such as giving conference presentations or posters, as well as academic paper writing – and, indeed, some EMP teachers do try to practice these skills with their learners. But also, due to the increasing frequency with which healthcare professionals move to new international locations for research or practice, the ability to use English as a working language (whether as host or as guest) has become a vital skill.

One of the functions required in such cases is the ability to make a clinical case presentation. These can be more formalized ‘conference-style’ presentations given within a hospital department or they can be the intense real-time conveyance of clinical data between two professionals during working hours.

Case presentations, like history taking, demand the use of critical thinking skills, the ability to organize data, the ability to grasp and express pertinence, and to separate such data from more peripheral items – in short, the management of specialized discourse. These skills too, when practiced in English, can have a washback effect on the learner’s first language or home working culture.

Horizontal English discourse skills can have an effect on the learner’s L1

What this means is not merely that EMP teachers should include case presentation skills in their syllabi, but that teachers should pay attention to how medical professionals actually communicate with each other in English-language settings. This would include having knowledge of which speech events occur most, among which types of clinicians, and to what ends and purposes. How are these events typically opened, managed, and closed?

Of course, in one’s home institution, these interactions will likely be conducted in the national language. But, for the sake of health professionals who will be going abroad or for those who will partake in international collaborations in the future, an ability to utilize the English of the workplace or the English of the internationalized professional will hold great benefits.

And even for those who do not plan to further their skills in an international setting, the increased awareness of clinical content, speech events, and interpersonal skills learned in English can carry over – or, again, washback – into one’s first language.

This horizontal axis of discourse deserves more exploration from EMP teachers.